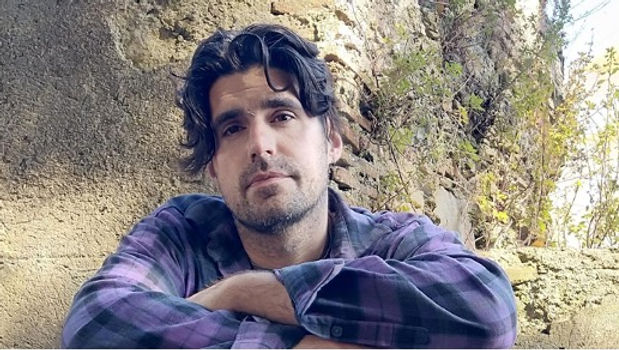

Conversation with Nicholas De Marino

Nicholas tells us about how his life experiences have impacted his writing, how he goes about writing his fiction, nonfiction, and poetry, and iterates the importance of word choice and poetic language.

Nicholas De Marino is a neurodivergent writer of fiction, non-fiction, not fiction, un-fiction, and semi-fiction. He has several writing credits, degrees, and accolades that have nothing to do with cats. Read more at nicholasdemarino.com.

Nicholas is the author of “the world ends with a whimper” from Issue 9.

Q: You received high honors from a reviewer a few days ago. What has been your relationship to reviewers throughout your writing career?

I'm tickled anyone reads my writing. Attention is precious. When I was a newspaper reporter, I only heard from people when I got things wrong.

That's not true, though. I wrote lots of fluff, so I got a confusing jumble of thank yous and angry letters to the editor. I still joke about plastering negative superlatives on my business cards—a favorite, in response to an album review: “This guy needs my Flying V shoved up his ass”—but, in truth, personal nastiness usually fuels stress eating and panic attacks.

Q: What led you to developing “the world ends with a whimper” as two couplet columns that can be read three different ways?

It started with parentheticals, not columns. (I use lots of parentheticals in early drafts.) Right before I turned forty, Red Ogre Review published my first poem, “It's Not Raining Yet.” Matt Bullen, the editor, shot back a whimsical version with alternating columns, like footsteps, to mimic the poem's rhythm. I liked the formatting, so I tried something similar for the second draft of “the world ends with a whimper.” For the third draft, I lined up the couplets across from each other. It felt like a running commentary, so I tried putting the voices in direct conversation. That didn't exactly work, either. Eventually, I settled on two voices monologuing over each other with the reader as the implicit third party braiding them together (or not). It seemed appropriate given the inspirational reference, i.e. the varied, disparate personal and societal themes in T. S. Eliot's “The Hollow Men.” Oh—and Virginia Woolf's “Mrs. Dalloway”! Especially the skywriting part. That's probably my favorite scene in all of literature.

Q: As a poet, how do you balance poetic language and being better understood?

Being understood is vital. But only at the end. I write to amuse myself and loved ones first, then proceed to sand off the rough edges. I'm only comfortable handing over a piece if you can tell which end is up. This often results in weird carpentry analogies.

Q: In what ways does your neurodivergence interface with your writing?

Two decades ago, I started writing for music magazines and content farms. I settled into newspapers, then started my own publication because I had no respect for the publication I was working for.

After that I took a few years off to have a nervous breakdown and come to grips with rampant ADHD, mild dyslexia, borderline OCD, and C-PTSD resulting from childhood neglect and abuse. Jotting down notes while drunk during a SIA twelve-step Zoom meeting was a low point, but I never hit bottom, proper. I'm still trying to figure out how all of this fits together.

Sometimes it feels like I'm writing cries for help. Other times all that comes out is manifestos. Other people tell me that's not how they do things, but it seems normal as hell to me. In terms of practicality, writing is feast or famine. I keep notebooks everywhere and change all the wording when I type things out. And there's always music going. When I wrote this, it was Slow Crush's Aurora. When I edited it: Coil's The Plastic Spider Thing.

Q: What do you describe un-fiction and semi-fiction as?

The bifurcation of fiction and non-fiction seems pretty arbitrary. There's a whole rainbow of gray between real and pretend with plenty of z-axis tangents. A lot of writing doesn't benefit from “reality tests.” Poetry, for starters. Hence, un-fiction. As for semi-fiction, well, I reserve the right to bullshit an answer about that in the future. Whatever it is, it's not “hybrid” though. That's just silly.

Q: What is 5enses, the alt monthly that you founded?

5enses is a publication in a town where I used to live. The surrounding area is a truly odd mix of retirees pursuing art, rehab centers, trustafarians, aviation plus tech people, tribal land, quality drag shows, a gun factory, and a genuine Tibetan Buddhist temple. Just think of all the possible cross-pollination! Sometimes it worked, sometimes it didn't.

The community (and, ahem, ahem, major advertisers) really leaned into nature and the outdoors. Science fiction legend Alan Dean Foster generously wrote a monthly column for us and totally nailed it. Genuinely kind human being. Ditto for John Duncan, the person who took the reins and still publishes it today.

Q: What is your relationship to Charles Bukowski, who you’ve mentioned in some of your poems?

Problematic. I won't play apologist for a sexist, abusive, drunk. But when I read his writing—especially the poems and the good half of the short stories—I really feel something. It's not always a pleasant feeling, but that's art.

The man knew himself, warts and all. And he voiced important, often ugly truths. There are benefits from separating the art from the artist, but it's usually foolhardy. I'll bring up Virginia Woolf again. Can you talk about “Orlando” without talking about Vita? Probably, but it wouldn't be as interesting or as honest.

Q: You write a self-described “rambling column” for foofaraw—what is your process for creating non-fiction, and how does it inform your poetry?

When I was a ham-and-egger reporter, I leaned on templates and cookie-cutter story forms to churn out three stories a day. Recognizing story elements is invaluable. For those columns, I just spew out every idea and reference in my addled head, no matter how convoluted or obscure. Then I cut, cut, cut, cut, cut. Kevin Kortum, the editor, is endlessly patient. This has very little to do with how I write poetry—mostly from wordplay and pet ear worms—but everything to do with how I edit it.

Q: How did the process of working as a journalist impact you?

Being a journalist gave me an impetus to overcome social anxiety and interact with people and the world at large. Every therapist I've ever gotten rid of shares the genius idea I should try that in my personal life. But no matter how many hours of D&D I log, I just can't roleplay being a reporter. I suppose it's a great way of grinding copy, but I know plenty of lifers still sending dispatches from the inverted pyramid. The kind of people who rattle off the spelling of Colombia the country versus Columbia the river but have never visited either. (I still count myself among this group.) I guess you've got to learn a rules system, any system, then break free from it.

Q: What has your experience as an English language tutor been? Do you think being a creative person is an asset when it comes to teaching a language?

If journalism taught me the power of choosing the right words, teaching English taught me the power of choosing the wrong ones. Communicating across language, culture, life experience, industry, and just about any -ism you can shake a hammer and sickle at requires more trust, empathy, and humility than just about anything. My job as a teacher is to help students express their ideas. That includes ideas I consider repugnant. This comes up daily. But, more often than you might expect, people are inquisitive, respectful, and, most importantly, open-minded. That gives me hope. Also, I get paid to make fart noises and talk about Minecraft with kids. Can we start this whole interview over? Reviewers should give writers hope. Let's start there.